I finally managed to wake up early enough for the morning sightseeing. The most anticipated temple of the day is the famous Kinkaku-ji Temple, also known as the Golden Pavilion. I planned on getting there when it opened at 9am. I wanted to see more, for sure, and since the Ryoan-ji Temple opens at 8am and it is in the vicinity of the Kinkaku-ji Temple, I decided to seize the chance and take a look at the Ryoan-ji Temple.

I headed west on a bus from Kyoto Station, Bus Route 26, and arrived at Ryoan-ji Temple a little after 8am. The admission fee to the Ryoanji-Temple is JPY ¥500.

A Brief History of the Ryoan-ji Temple

Meaning “the temple of the dragon at peace,” Ryoan-ji Temple was originally the villa of the Fujiwara family during the Heian period. Fujiwara Saneyoshi built the first temple on site, the Daiju-in, and the large pond in the family estate in the 11th century.

The powerful warlord, deputy to the shogun, Hosokawa Katsumoto, acquired the land in 1450 and built the Ryoan-ji Temple. The Ryoan-ji Temple is a Zen temple. It is undisputed that the original temple was destroyed during the Onin War between the clans. Hosokawa Katsumoto’s son rebuilt the temple in 1488.

Perhaps of a more modern relevance is that Queen Elizabeth requested to tour the Ryoan-ji Temple in her visit to Japan in 1975. She had high praise for the beauty of this temple.

A Tour of the Ryoan-ji Temple

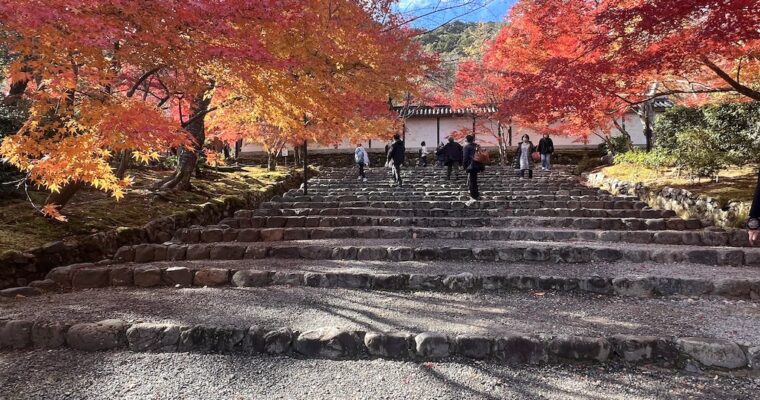

The Ryoan-ji Temple was tranquil. At that early morning hour there were very few tourists, and I could walk around in peace. There are three main sites to see: the famous Rock Garden, the large Kyoyochi Pond and the garden space.

Due to time constraints, I did not go inside the Ryoan-ji Temple because, like so many other temples, shoes must be taken off to go inside. The Rock Garden is a famous classic Zen garden.

Kyoyochi Pond, meaning “mirror-shaped pond,” comes with a half loop to walk around. There are three small islands on the pond. Two of these islands are reachable by walk.

There are many beautiful gardens in Ryoan-ji, but I could only do a very hurried walk amongst them. Suffice to say, her Majesty the Queen was certainly right about the Ryoan-ji Temple’s beauty.

A Word about Zen Gardens

In a later entry, I will be discussing the particularly famous Zen gardens in the temples of Kyoto. The creators of Zen gardens usually introduce some ideas about the imageries being presented at these gardens. But the experience of viewing a Zen garden is largely meditative, and despite the intentions of the creator, one is encouraged to find his or her own zen in the experience.

As karesansui, a Japanese dry garden usually comes in the imagery of pebbles as the water and includes natural elements such as moss, pruned trees and bushes. Sand and gravel with raked curves represent the ripples of the water. These imageries are meant to convey the very essence of nature. White sand and gravel are usually prominently featured on the ground. In Shinto, they represent purity.

In temples, the Zen gardens are usually viewed from a porch, as a seating area extended from the floor of the temple. The viewer of the Zen garden usually gets a unilateral view of the carefully curated gardenscape. At the Ryoan-ji Temple, the Rock Garden is best viewed from the centre of the Hojo.

The Ryoan-ji Temple’s rock garden features “a rectangular plot of pebbles surrounded by low earthen walls, with 15 rocks laid out in small groups on patches of moss. An interesting feature of the garden’s design is that from any vantage point at least one of the rocks is always hidden from the viewer.”

While classic Zen gardens, especially that of Kyoto, are believed to have arisen during the Muromachi era of the early 14th century (also the under the Ashikaga Shogunate ruling from Kyoto), the idea of stone gardens in Japan arose at least as early as the Heian period of late 8th to 12th century.

Red foliage lined the garden and the large pond. I had an exceedingly pleasant walk in Ryoan-ji Temple. The views were heartbreakingly beautiful, as if nature wrote a love poetry to itself.

Sources

The Wikipedia on Ryoanji.

The Wikipedia on Japanese Dry Garden.