The Jao Tsung-I Academy celebrates and memorializes the legendary life of Jao Tsung-I, a sinologist of many talents in arts and history. I took a walk at the venue and joined a public tour.

The Life of Jao Tsung-I

Jao Tsung-I was very accomplished in Chinese learning and fine arts. Born in Chaozhou (Chiu Chow), Jao Tsung-I came from an incredibly wealthy family that had 4 banks. His mother died when he was just 2 years old. At 11 years old, he stopped formal schooling. Instead, he just learned by reading in his home library. His father wrote a book on Chiu Chow. When he was 16, his father died. Jao took over the book writing.

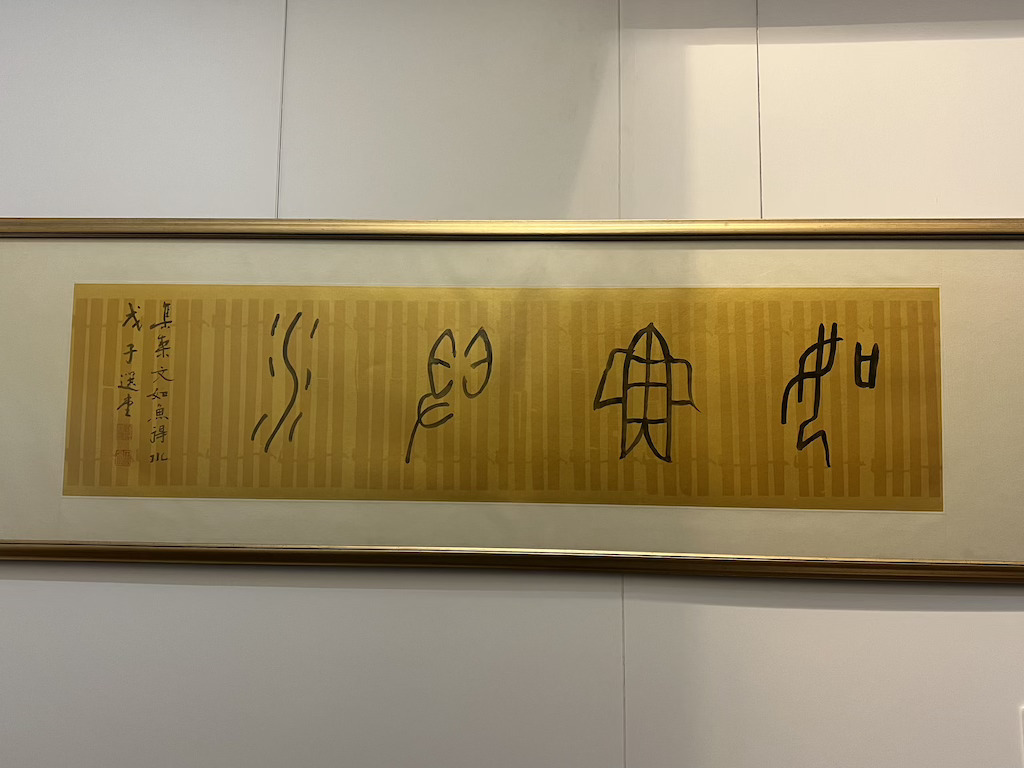

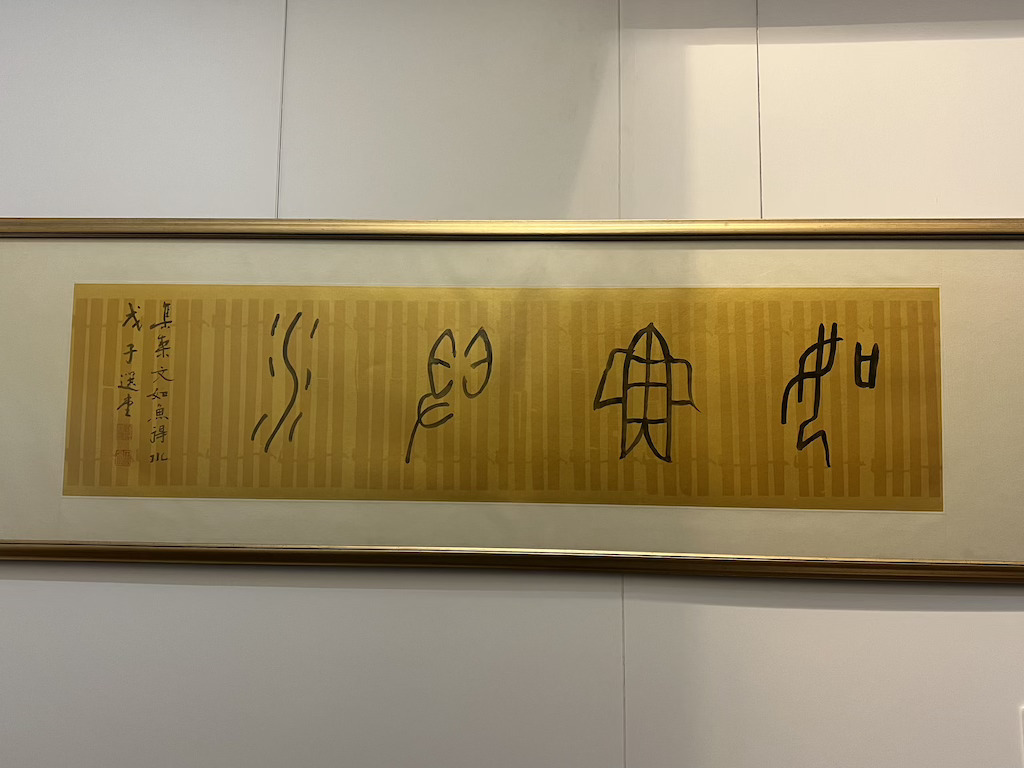

At age 22 he became a researcher in Sun Yatsen University. In Hong Kong, he brushed shoulders with the literati. In 1949, he immigrated to Hong Kong. At age 35, he was already a professor at University of Hong Kong on classical literature, with research in a broad spectrum of historic Chinese interests such as dance, music, classical Chinese, the arts, and oracle script. Much of the learning in these academic fields are reflected in his artwork. He dedicated his life to the learning and teaching of classical Chinese. Innumerable awards and honors have been conferred to him for his work.

Photo above: The most significant artwork of Professor Jao.

Jao Tsung-I passed away at the very advanced age of 100 in 2018. He did live to see the day of opening of the Academy that celebrates his life. He left behind a rich heritage that constitutes the core substance of the Jao Tsung-I Academy today.

The Architectural Features of the Jao Tsung-I Academy Clusters

There are three sections in the Jao Tsung-I Academy. The very upper section is up on the hill. With five buildings there they are now serving as the Heritage Lodge, a hotel. In the middle section, the buildings were once the wards for the prisoners and the patients.

In the Lower section, the blocks retain their original red brick appearance. Together these buildings have had a long history in serving various purposes for the government and the community throughout its 114 years, pretty much as the needs arose.

As the former Lai Chi Kok Hospital, the structures of the Jao Tsung-I Academy were built between 1921 and 1924. All of the structures are of red brick, a common feature for colonial-era buildings in Hong Kong. Due to its history serving as healthcare and prison institutions, including as the quarantine center for infectious deceases, the buildings in the middle and upper sections were reinforced with very heavy layers of concrete and sealed with white paint.

During the restoration, effort was made to remove this thick layer of concrete and its white paint in the former wards of the middle section, as a means to reveal the very original face of the blocks. However, it proved to be too difficult to do so for all six blocks. Therefore, only the middle block shows the part of original red bricks now. The buildings in the lower section show the original red brick structures, as they served mostly as staff quarters and administrative units during the Academy’s former lives.

Photo above: This photo shows the parts of the red brick walls that were revealed after removing the concrete and the white paint during the restoration, as an illustration of the original appearance of the blocks in the middle section.

Architecturally, the red brick buildings are eclectic in style due to the combined use of the red bricks and the traditional pitched roofs showing double Chinese tiles.

The former hospital and prison wards in the middle and upper sections were of the utilitarian design, with external staircases in most of the blocks.

The History of the Jao Tsung-I Academy

Photo above: The small garden pond in the lower section was carefully designed.

Most parts of its history do come with some stigma. In its long succession of many different roles, Jao Tsung-I Academy had been the a quarantine station for approaching vessels, Lai Chi Kok Prison, a specialist hospital for infectious deceases (including leprosy), a psychiatric hospital, and a psychiatric rehabilitation center in the 20th century.

The former Jao Tsung-I Academy stood on the coastline before the reclamation of the Mei Foo area. Its location in this part of Kowloon west also bears upon its previous role in the community. During the late 19th century, the Qing government had set up a customs station close by, called Kowloon Customs. The stone plaque with the inscription “Kowloon Customs Boundary” stands at the east hillside of the site as a testament to this early history.

Amongst the older generation of Hong Kong people there is this common phrase “being sold off as piglets,” referring to the practice of sending off people to do manual labor in foreign countries, as coolies. During a brief period of two years in the early 19th century, the British firm Swire (Taikoo) borrowed the name of The Chamber of Mines Labour Importation Agency and built “pigpens” at the former Jao Tsung-I site. This location served as the laborers’ quarters for those who would be ready for involuntary or voluntary servitude. The workers were held here before they were being sent off to sea at the pier very nearby. Many of those workers were heading off for the gold mines of South Africa.

As the Lai Chi Kok Prison, the Jao Tsung-I Academy took in the prisoner population that crowded the Victoria Prison. It had a good reputation despite being a place of confinement. The Lai Chi Kok Prison was considered a “model prison,” with rehabilitation as its objective. The conditions and treatment here were humane. Female prisoners could raise their children here for three years.

The Jao Tsung-I Academy Today

In 2008, the Antique and Monuments Office gave the Jao Tsung-I Academy a rating of Grade 3 Historic Building. The revitalization of the Jao Tsung-I Academy was the very first batch of projects under the government’s Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme, which began in 2008. The partner in this revitalization effort is the Hong Kong Institute for Promotion of Chinese Culture. As it is named after a preeminent sinologist, the Jao Tsung-I Academy is now the venue for cultural and educational activities.

On-site facilities include multiple museums displaying the arts of Jao Tsung-I himself, a Heritage Hall explaining the history of the site, a higher-end restaurant serving western cuisine (House of Joy), a smaller coffee shop (Timeless Café), and a heritage hotel that welcomes pets. The former prison and hospital wards now serve as the cultural space, showcasing exhibitions and holding seminars for a rental fee.

Beyond the initial contribution by the Hong Kong Government, there is no more subsidy for the running of the Jao Tsung-I Academy. It is operated as an NGO with self-sufficiency.

How to Get There

The Jao Tsung-I Academy is located on 800 Castle Peak Road. Although most people think that the only way to get there is to walk from the Mei Foo MTR Station, there are actually many bus routes (heading the Shatin direction) that stop right outside of the Academy. Please see above picture showing you the bus routes.

Sources

Descriptions on site at the Jao Tsung-I Academy.

Public tour at the Jao Tsung-I Academy.

The website of the Jao Tsung-I Academy.