This was not the first time in Thailand for me, but surely my first time visiting Bangkok. My last trip to Thailand was more than a decade ago in Phuket.

I was quite excited about this trip because it was organized by my uncle with luxurious plans in top notch accommodation and dining. We would be staying at the high-end commercial area developed by the Erawan Group and the Central Group, our hotel of choice was the Grand Hyatt. The rest was all about enjoying ourselves with great company and fantastic food.

First Impressions of Bangkok

We touched down in Bangkok on a slightly overcast day. It was a Saturday but we were told to expect a bit of traffic from the airport to the Grand Hyatt Erawan. And true to the word, we were stuck in traffic in one end of the street for 20 minutes before making it to the other end of the street. It turned out that the traffic of Bangkok would be the single most annoying aspect of travelling in Bangkok. We had a hired driver throughout our stay, therefore we were not going to get on public transportation at all. As such, we were very often stuck in traffic at this busy and posh area of town.

It turned out that the traffic of Bangkok would be the single most annoying aspect of travelling in Bangkok. We had a hired driver throughout our stay, therefore we were not going to get on public transportation at all. As such, we were very often stuck in traffic at this busy and posh area of town.

We immersed in all the luxuries that Bangkok had to offer to those who could afford it. And most could afford them, for prices tend to be affordable in Thailand.

The Grand Hyatt Erawan Hotel

We arrived at the dazzling world of the Erawan group as the hotel enveloped its visitors with endless Christmas charm. Christmas was maybe two weeks away, but the Buddhist country spared no effort in propping up the lavish appearances of a celebratory spirit that would appeal to visitors of the western world.

The Erawan Group runs a host of businesses in hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail and office rental in Thailand. As a leader of the hospitality business in Thailand, Erawan offers the full range of hotel options for visitors, from the luxury line to the very basic budget choices.

The Grand Hyatt is considered a luxury option under the Erawan Group. It does have a reputation for being haunted, however. The group of six businessmen that were murdered by poison (including the murderer’s own suicide) died in one of the villas in the Grand Hyatt in 2024. This made international news.

But people are naturally forgetful. When we checked in the hotel, we sensed in this festive atmosphere a business-as-usual vibe. We were not staying at the villas either, so I eagerly checked into a standard hotel room and enjoyed the comfort throughout my stay there.

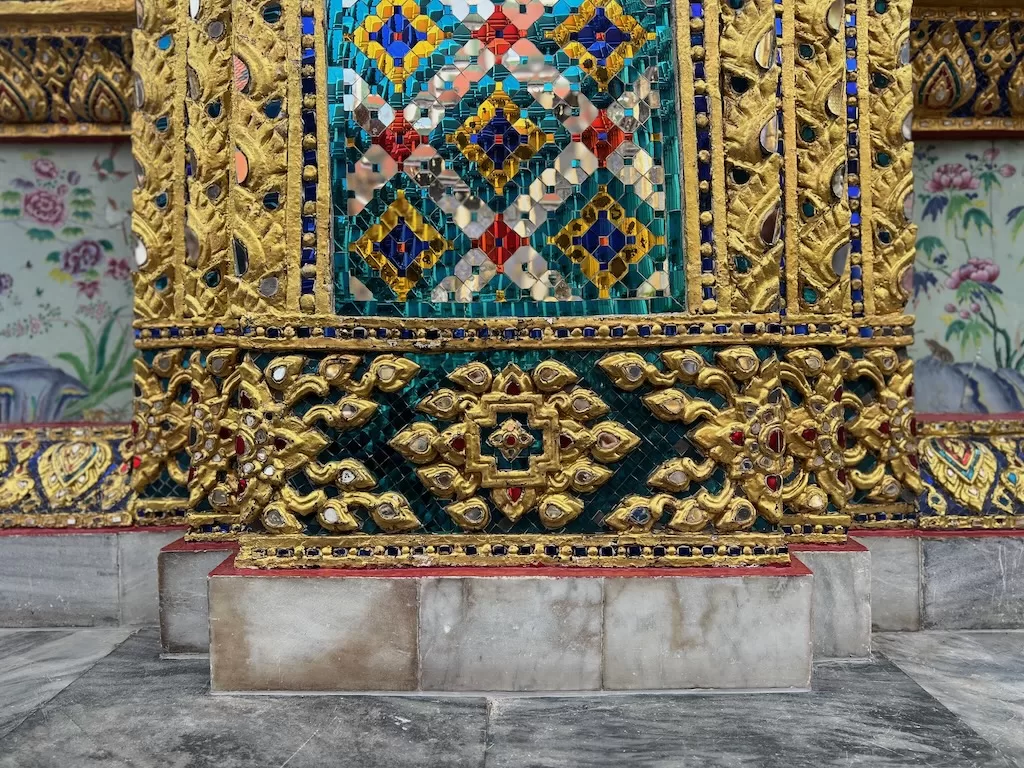

The Erawan Shrine

Most followers of Buddhism would be very familiar with this area of Bangkok because the frequented Erawan Shrine lies right next to the Grand Hyatt. The sinews of the Buddhist faith reveal themselves fully in this street corner. We viewed the Erawan Shrine from the footbridge overlooking the intersection of Ratchadamri Road. The Erawan Shrine drove the movement of foot traffic, in and out, a stream that flowed consistently at any time of the day.

Worshippers of Phra Phrom, the resident deity at the Erawan Shrine, come in throngs to tender their tributes. Phra Phrom is a Thai representation of Brahma, the Hindu god of creation.

In Hong Kong, people refer to this Buddha as “the four-faced Buddha,” each of its face representing one aspect of life. First is work life, then wealth, health and money. Suffice to say, that these are indeed common pursuits for most human beings.

In the worship, followers would prepare incense, lotus flower, candles and water for their tender. “The deity is popularly worshipped outside of a Hindu religious context, but more as a representation of guardian spirits in Thai animist beliefs, nevertheless the shrine shows an example of syncretism between Hinduism and Buddhism.” (erawanbangkok.com)

Being Christian, however, I preferred to remain in the grand festiveness that the hotel has put together for its western guests. It felt much closer to heart for me than the Phra Phrom next door.

Spa, Spa and More Spa

In the plans were a few spa sessions in our four-day stay. I visited two spas, and both were quite good. Of the two spas, I preferred Diora, as my massage therapist nailed my pressure and pain points with much better precision at Diora.

Diora

Infinity Wellbeing

Siam Satiety — Ambrosia Overload

Dining in Thailand comes at a fraction of the cost in Hong Kong. This is the reason why Bangkok is an exceedingly popular vacation choice for Hong Kong people. We had quite a few meals at the Grand Hyatt restaurants, a private kitchen experience at a heritage building in the Mandarin Oriental, and a couple meals in the malls.

Be it western cuisine or the local flavors of Thailand, be it fine dining or street food, all the food we had were perfectly delivered with memorable highlights.

This first trip in Bangkok opened my eyes to a stellar array of Siam’s ambrosia. The western cuisines show a firm dedication to authenticity. The Thai specialties feature charming repertoires of Thai spices, bringing to the palate a harmonious fusion of complex flavors. There will be a food entry in this series.

Sources

Erawanbangkok.com on the Erawan Shrine.

The official website of the Erawan Group.

It turned out that the traffic of Bangkok would be the single most annoying aspect of travelling in Bangkok. We had a hired driver throughout our stay, therefore we were not going to get on public transportation at all. As such, we were very often stuck in traffic at this busy and posh area of town.

It turned out that the traffic of Bangkok would be the single most annoying aspect of travelling in Bangkok. We had a hired driver throughout our stay, therefore we were not going to get on public transportation at all. As such, we were very often stuck in traffic at this busy and posh area of town.