Ubiquitously Uzbekistan – The Shah-I-Zinda, Crown Jewel of Samarkand

We took a quick lunch at the Siab Bazaar and then headed toward the Shah-I-Zinda. On our way, we passed by the Hazrati Hizr Mosque.

The Hazrati Hizr Mosque

The Hazrati Hizr Mosque was built in 1823. Although as compared to the myriad other ancient structures in Samarkand it may have paled in terms of historical significance, it stands on a site that represents a legend.

According to Central Asia Travel, “The mosque was built on ancient foundations, and historical written sources (and later archaeologists confirmed this) say that in the XI century the very first mosque in Samarkand was erected here: ‘on the place where Muslim banners were located.’” Hizr was a holy elder that people worshipped, even as early as the pre-Islamic times. He was the patron saint for the travelers.

The Hazrati Hizr Mosque sits on a hill with a gentle incline. It shows beautiful architecture, in particular the arched iwans. Look up and you will see a beautiful wooden framed roof well-adorned in cheerful colors.

Out on the side porch one can have a full view of the Bibi Khanym monuments afar.

Suffice to say, calls to prayers are still active at the Hazrati Hizr Mosque. In fact, for some sections of the mosque photography is forbidden. Please respect that prohibition.

The Sha-I-Zinda

By the time that we were done at the Hazrati Hizr Mosque, the sun came out and greeted us with a warmth that we missed since the morning rain.

The Sha-I-Zinda is a necropolis housing the burials for a number of both holy and royal persons. More than twenty mausoleums for known and unknown persons line the complex, along with a number of mosques. The Ulug Bek Pishtaq was Ulug Bek’s contribution in or after 1434 and invites visitors into the necropolis on a grand entry.

But there was nothing quite so out of the ordinary for this introduction of the necropolis. The initial structures, including the chortak’s (domed transition halls) are beautiful but not unlike what we have seen so far. We passed by a series of “other structures.” We then climbed the Staircase of Sinners.

When we reached the first group of mausoleums, we could not help but to marvel “wow.” And then we fell silent. The beauty before our eyes took our breaths away. We were overwhelmed, mesmerized beyond words. My friend and I parted our ways here, drawn to the view of every perspective of these monuments that we each found appealing.

The first four mausoleums that line the two sides of the avenue of the dead left an indelible impression. I was, simply put, blown away. And the pictures here do not fully convey that sense of marvel at the first sight of this grandeur. It also helped that I had not looked at images of Sha-I-Zinda before I went, and the mystery was under wraps until the complex stands tall and imposing before me.

The History of the Shah-I-Zinda

In my opinion, the Shah-I-Zinda is the crown jewel of Samarkand.

Shah-I-Zinda, meaning the “Living King,” is a complex of mausoleums built between the years 1360 and 1434. There is one burial that was considered sacred throughout Samarkand’s history, and that is, first and foremost, the tomb of Kusam Ibn Abbas, a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad. Legend has it that he arrived in Samarkand during the pre-Islamic period. His preaching was effective and angered the pagan worshippers. They beheaded him, but apparently he picked up his head and walked into this area. People believed that he lived to this day.

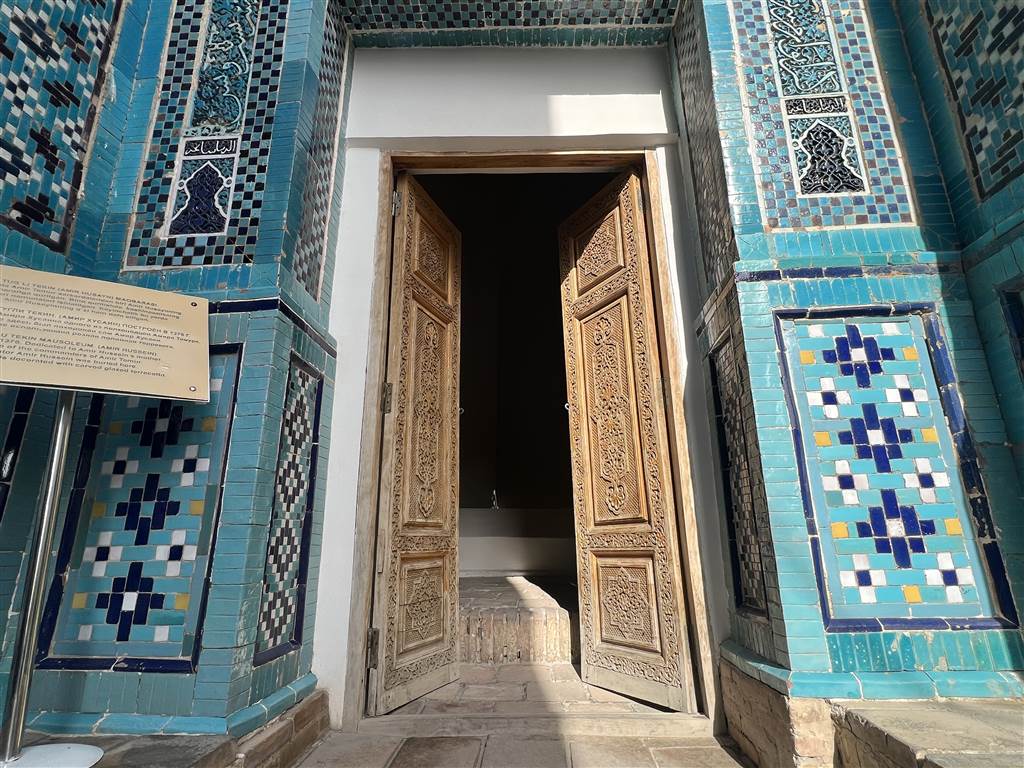

The Timurids then continued to build their royal tombs surrounding the scared site during the 14th and 15th centuries. Amongst others, there was the Tuglu Tekin Mausoleum, built in 1376 and dedicated to Amir Hussein and his mother. Amir Hussein was one of Amir Timur’s generals. The 1386 Amirzoda Mausoleum was dedicated to one of Amir Timur’s sons. These are the first two mausoleums across from each other.

The next two mausoleums are perhaps better known for their elaborate adornments. The Shirin Beka Oka Musoleum (1385, on the right) and the Shadi Mulk Aka Mausoleum 1372, (on the left) are dedicated to Amir Timur’s beloved female members of his family. The Shodi Mulk Oko Mausoleum bears an inscription “This is the tomb in which a precious pearl has been lost,” where Amir Timur’s beautiful niece and her mother lie in rest. The Shirin Bika Aka Mausoleum is the burial for a sister of Amir Timur.

Go on and you will see many more such beautiful mausoleums in the complex.

Photo: The Octagonal Mausoleum houses the remains of an anonymous person.

Be sure to also admire the interiors.

There Is A Secret

In one of the crypts, I overheard a tour guide telling an interesting story to his tour group.

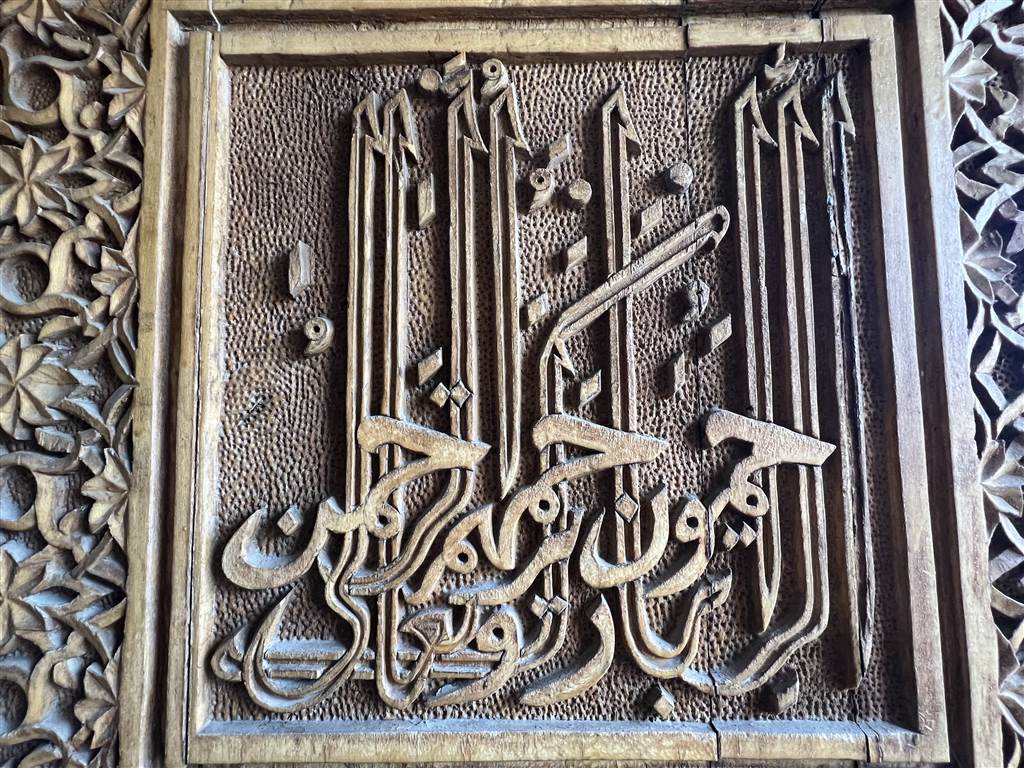

Hidden in the crypt’s typical band of Arabic inscriptions, there is a secret. The secret was told to the craftsmen that built the mausoleum and it was supposed to be encrypted into the Arabic inscriptions. But it was eventually lost because all the craftsmen were killed in the end, in order to preserve that secret.

I guess myths and mysteries of morbidity arise naturally during the process of building a necropolis of such scale. This story reminds me of Amir Timur’s curse, which we learned the day before at the Gur-I-Amir.

The Architecture of the Shah-I-Zinda

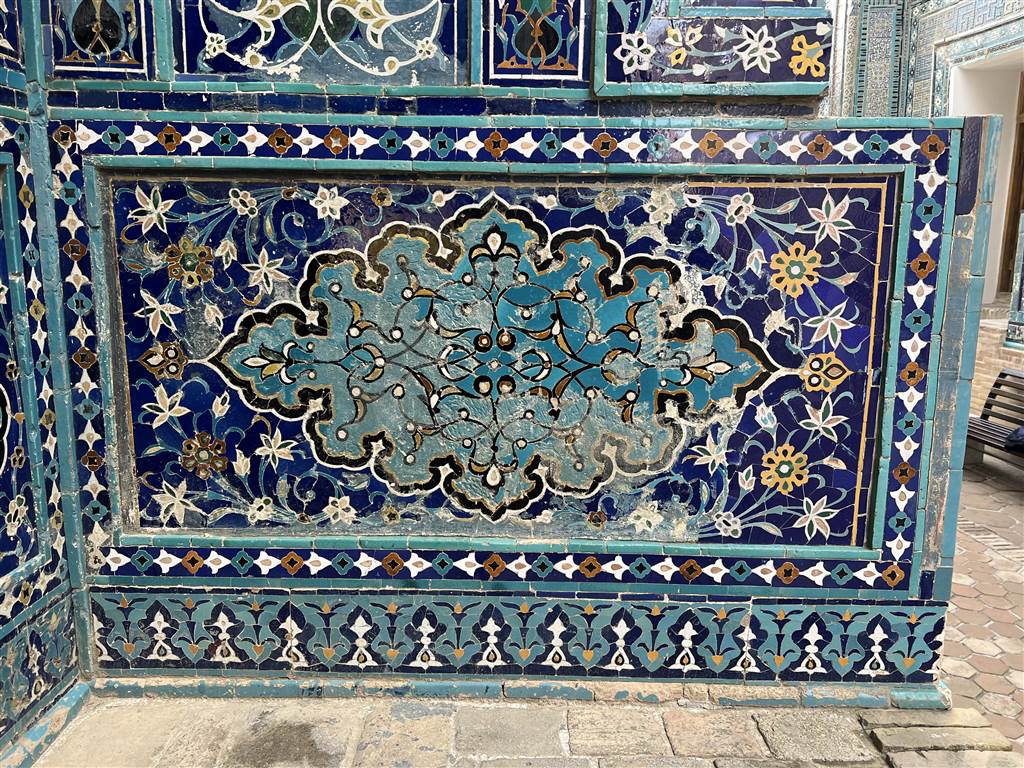

There is that unifying theme of the turquoise, marine and azure blue on the mausoleums’ portals, plus the typical earthy tones in the plain bricks that made the other structures in the Shah-I-Zinda Complex, but the similarities end there. The adornments of each mausoleum are notably different, as they were each built in different times and adorned by different architects.

In terms of adornments, these mausoleums showcase every technique of Islamic architecture that existed in those times of antiquity and exhibit the height of craftsmanship that has enabled such grandeur. Tile mosaics line the blue base tone in the front portals of these monuments, in glazed ceramics, terracotta and majorlica.

Glazed bricks and carved wood also show prominently in some of the structures. In the Shodi Mulk Oko Mausoleum, “the most elaborate and most spectacular is that of pierced glazed tile décor which combines delicate sculptures with the subtle transparencies of glazing.” (Dominique Clevenot at 99).

A good walk at the Shah-I-Zinda must take at least two to three hours, in which time you will marvel at the beauty of the structures, one after one.

We went in the late afternoon. Around 3pm or so, there were a whole lot of tourists and that made photography difficult. However, by around 5 or 5:30, most of the crowds will have left. Indeed, many tourist sources suggest that the best time to go to Shah-I-Zinda is during the late afternoon, early evening.

Sources

Descriptions on site as the Shah-I-Zinda.

Sophie Ibbotson, Uzbekistan, Bradt Travel Guide (2020).

Calum Macleod, Uzbekistan: the Golden Road to Samarkand (2014).

Moya Carey, An Illustrated History of Islamic Architecture (2012).

Dominique Clevenot & Gerard Degeorge, Ornament and Decoration in Islamic Architecture (2000).