Ubiquitously Uzbekistan – The Registan of Samarkand

The Registan of Samarkand is the very soul of the ancient city’s heritage. Standing majestic in the heart of Samarkand, the Registan has witnessed the turns of history that shaped the ancient city as well as Uzbekistan. Its historic presence represents Samarkand’s legacy as an ancient oasis along the silk road, and the Timurid dynasty’s commitment to culture, governance and learning.

The Registan, meaning “a sandy place,” is the central public place in a given ancient city in Uzbekistan. It served multiple purposes for the ancient citizens of Samarkand. Trade, culture, official administration and Islamic learning in the Registan were breaths of civility that brought Samarkand the grandeur that it stands for today. And as we found out later in the day, this breath of civility would renew in a modern vein.

A Brief History of the Registan in Samarkand

During Amir Timur’s lifetime, activities at the Registan were mostly commercial in nature. There were six main roads that ran through the square. The square was also connected to Amir Timur’s citadel by these roads. There used to be a domed bazaar, but Amir Timur’s grandson Ulug Bek ordered the construction of the Ulug Bek Madrassa, thus perhaps permanently changing the character of the square into historical and cultural. Surely, throughout its ancient existence the open space was often the site for military parades, the public announcement of royal edicts, or even where executions took place, but it was always the heart of all things important for the citizens of Samarkand.

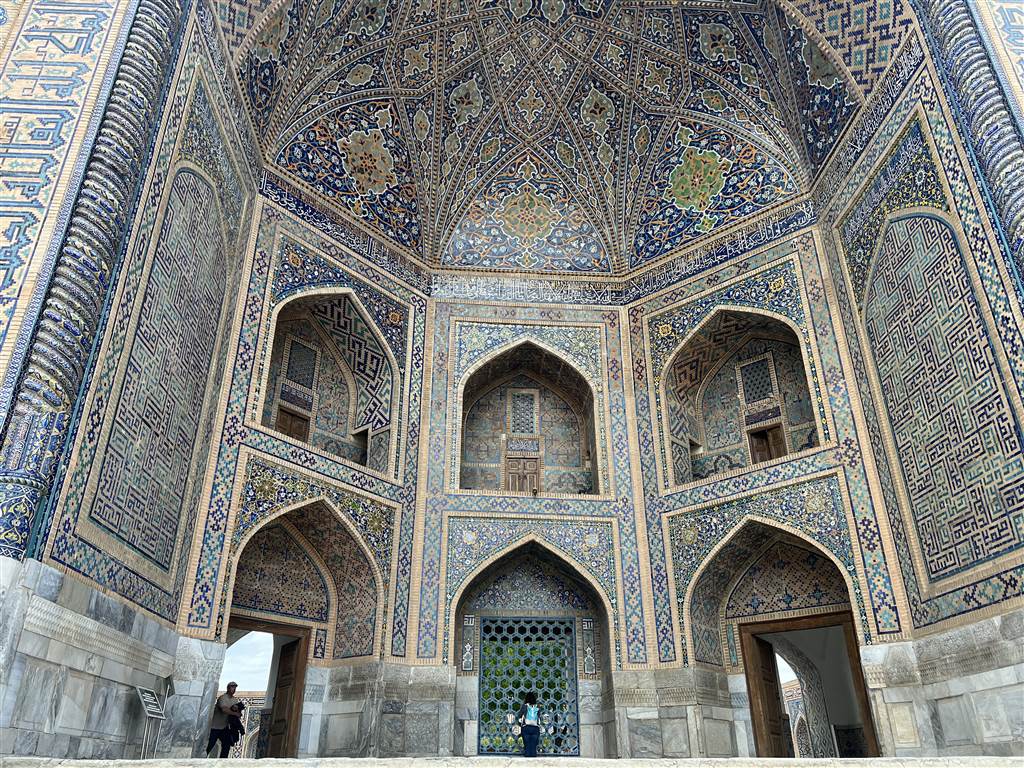

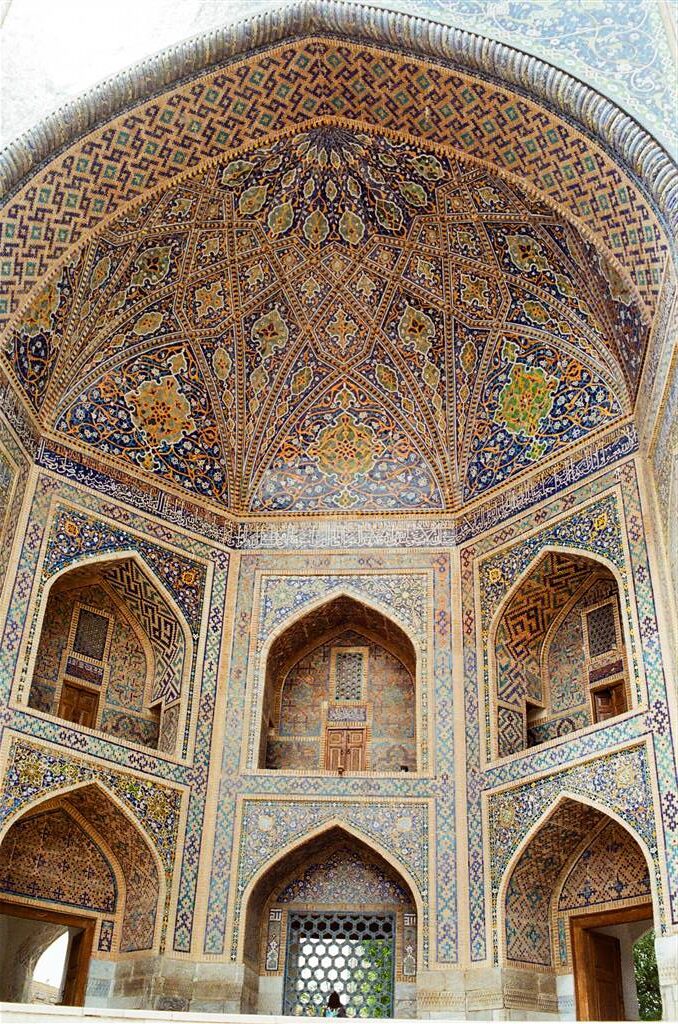

The three grand structures that make the ensemble at the Registan are namely, the Ulug Bek Madrasa to the west (on the left, if you stand on the viewing platform), the Tillya-Kari Madrasa to the north (in the center), and the Sher Dor Madrasa to the east (on the right).

The Ulug Bek Madrasa

The Ulug Bek Madrasa was a work of Ulug Bek between 1417 and 1420. In many ways the architectural designs of the building reflected the learned nature of Ulug Bek himself, especially in all things scientific and astronomical. Against the background of earthy toned bricks are set turquoise glazed tiles laid out in mosaics, their patterns representing the stars in the sky. At a total height of 45 meters the front portal drawfs all human presence in the square.

As a standard design in Islamic architecture, the Kufic inscription declares the magnificence of the architecture itself, “This magnificent façade is of such a height it is twice the heavens and of such weight that the spine of the earth is about to crumble.”

The Ulug Bek Madrasa provided 50 rooms for student accommodation (each room typically housed two students). As an educational institute, the Ulug Bek Madrasa did not limit itself to religious instruction. Students engaged in secular studies, especially in science and astronomy.

The Tillya-Kari Madrasa

By the 17th century, the Mirzoi caravanserai (an inn denoting a resting and trading place for merchants, but most likely this caravanserai served pilgrims) that Ulug Bek built on this site lied in ruins. The ruins of the Bibi Khanym Mosque was also viewed to necessitate a new site dedicated to Islamic learning and worship. As such, Baohir Yalangtush commissioned the Tillya-Kari Madrasa, which includes both a madrasa and a mosque. The building construction completed within a 14-year period in 1660.

Meaning “the Gold-covered Madrasa,” The Tillya-Kari Madrasa has the most elaborate appearance in its pishtaq (front portal) in my opinion. The tile mosaics fully cover the whole brick underlay. They exhibit intricate patterns that are lavish, with a touch of sophistication that somewhat differs from that of the Ulug Bek Madrasa.

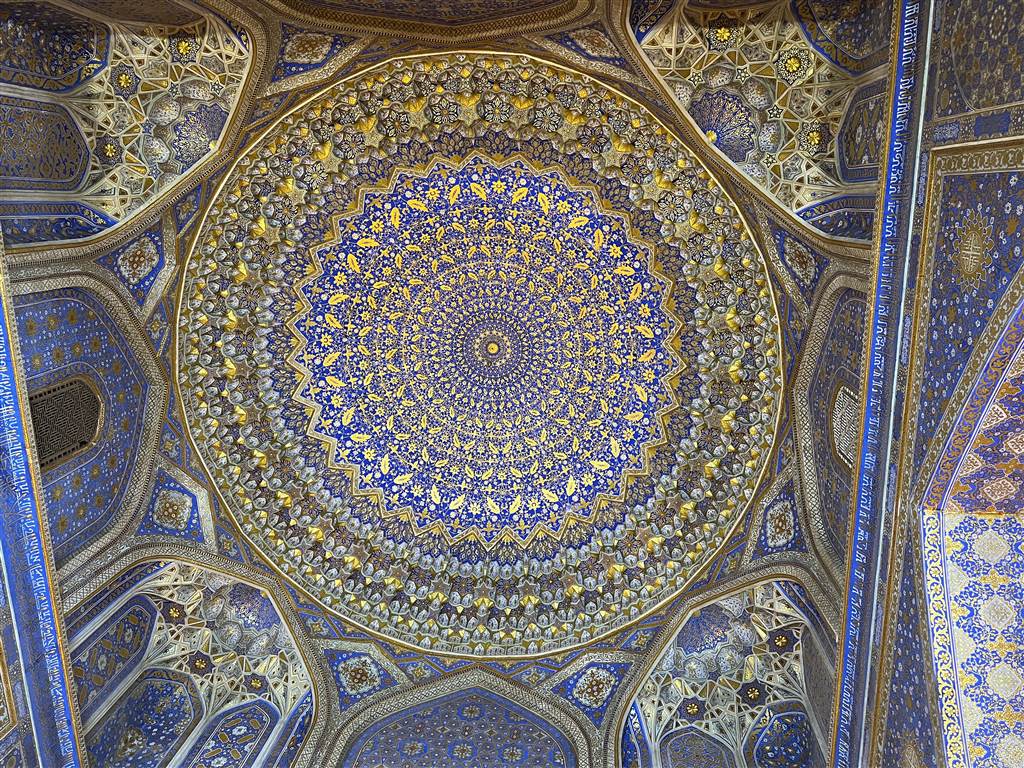

The name of the Madrasa came from the decorated interior of the dome, which is gilded in gold leaves. Therefore be certain to check out the interiors of the monument, and look up at the marvel of Uzbek architecture.

Unlike the Ulug Bek Madrasa, where students participated actively in secular learning, the Tillya-Kari Madrasa was conceived with a purely religious purpose. The mosque was for congregational worship.

The invasion by Nadir Shah in the 18th century damaged the dome. Restoration of the dome was only completed in the 20th century.

The Sher Dor Madrasa

Meaning “with lion,” the Sher Dor Madrasa was built by the 17th century mayor Bahodir Yalangtush in Samarkand between 1619 and 1636. The key difference between the Sher Dor Madrasa and the Ulug Bek Madrasa is that there is no mosque in this structure. It provided 52 hujras (student rooms) for students.

In terms of design features, the Sher Dor breaks with Islamic tradition in a key way. Figures of lions (or two felines with lion manes and tiger stripes at the same time) do appear in its pishtaq. Islamic architecture and art typically shun figurative representations of animals. There are very few other examples of this break with Islamic tradition. However, in Bukhara’s Lyab-i Hauz ensemble simurgh birds also adorn the pishtaq of the Nadir Divan-Begi Madrasa.

According to Calum Macleod, “legend claims the architect responsible died for his heresy.”

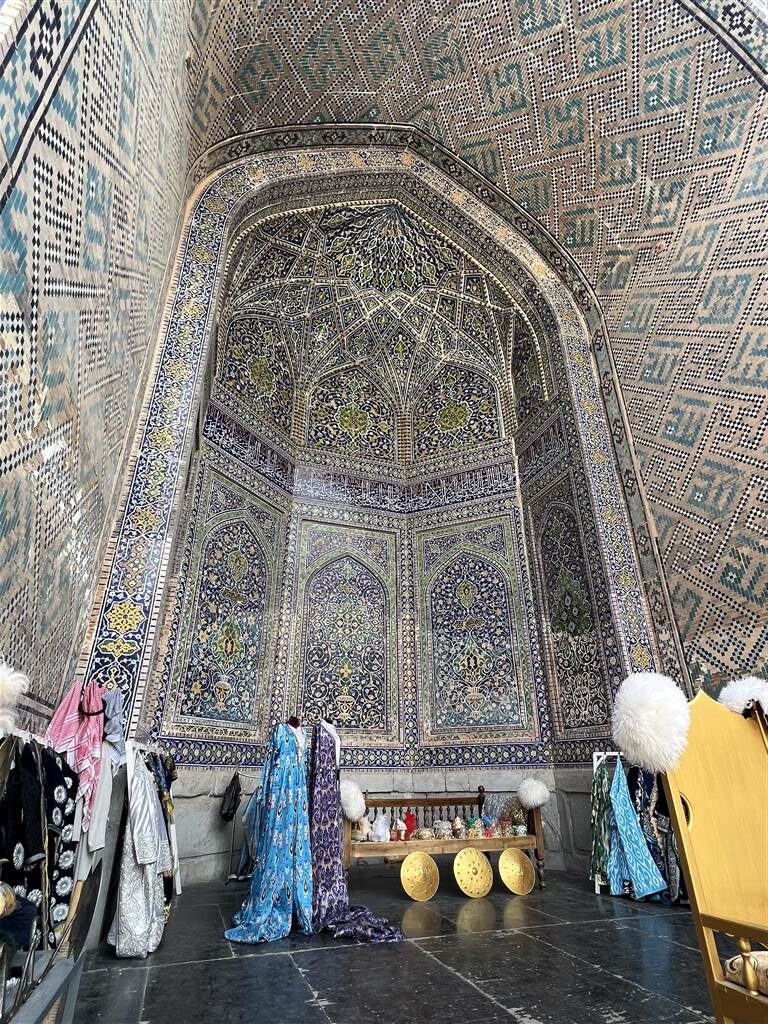

These three monuments were all lying in ruins by the 18th century. At some point they became the grain storage for Samarkand. In the 19th century, a religious revival again called attention to their significance. Perhaps not surprisingly, the original student rooms at these madrasas are now the small shops for souvenirs and art galleries.

A Wonderful Afternoon Coffee at the Registan

We went through the three structures respectively and by late afternoon we were desperate for a break. There is a coffee cum souvenir shop at the Ulug Bek Madrasa on the second floor. We decided to grab a table and had our afternoon coffee. The owner told us that it was a prime spot for pictures and so he snapped a few very good shots for us. It is such a wonderful experience relaxing amidst the very epitome Samarkand’s grandeur.

The Registan Today

During the warmer months, there is a light show that illuminates the Registan in all colors of the spectrum in every evening. The light show comes at 8 to 8:30pm or so and it goes for about an hour. The lights presented the Registan in an incredible glamor. We stood completely absorbed in the accompanying Uzbek music that celebrated Samarkand. One song rang in our ears repeatedly all evening. We did not understand anything else in the lyrics, except for “Samarkand, Samarkand” sung repeatedly.

One would take a spot at the elevated viewing podium that faces the middle of the public square. It offers a full view of the Registan. Its plaza being enclosed on three sides by imposing monuments, the Registan as an ensemble has centuries’ worth of history behind. We took just a few steps beyond the viewing podium, hoping to take an even more embracing view of the Registan’s grandeur, and only then did we see clearly why there was a crowd sitting at tables before the public square.

The people of Uzbekistan were having a chess tournament that evening. No, it was not chess playing that was the breath of civility that renewed in a modern vein. Amir Timur himself was a serious chess player. What made chess playing a modern vein was rather the tournament. We witnessed the very essence of community that evening at the Registan. The gaming spirit united people from all walks of life. From men to women and from girls to boys, they all gathered under the colors of the Registan and played to the music of their pride.

When we went, we observed many, many Uzbek tourists, especially young students touring in large groups. Some of them asked to take photographs with us. We thought they were rightly proud of their heritage as amply shown in these monuments at the Registan.

Allow a good few hours, perhaps a whole afternoon, for a thorough walk in the structures of the Registan. The picture-taking itself will be time consuming, because of the throngs of tourists there fighting for the prime photo spots. Of course, reserve time after dinner to come back for the light show. It was one of the most amazing experiences I had in Uzbekistan.

Sources

Uzbekistan.Travel on Registan Square.

Descriptions on site at the Registan of Samarkand.

Moya Carey, An Illustrated History of Islamic Architecture (2012).

Sophie Ibbotson, Uzbekistan, Bradt Travel Guide (2020).

Dominique Clevenot & Gerard Degeorge, Ornament and Decoration in Islamic Architecture (2000).