Ubiquitously Uzbekistan – The Gur-I-Amir of Samarkand

There is speed rail in Uzbekistan.

We made it to our 7am train to Samarkand. About two hours later, we arrived in Samarkand. From the train station we took a taxi to Bahodir B&B, where we would stay for two nights until we headed out onto the next leg of the journey in the Nuratau Mountains.

As we went on with our tour of Samarkand, the level of sophistication and grandness of the sights would also progress, culminating in the final scenes at Sha-i-Zinda. But that is for a later entry.

The Gur-I-Amir

A Brief History of Gur-I-Amir

With excitement we headed out for our first sightseeing. From Bahodir we walked about 20 minutes to reach the Gur-i-Amir (meaning Lord’s Tomb, the Mausoleum of Amir Timur). Of the sights that we visited in Samarkand, Gur-i-Amir was perhaps more “down to earth” in its appearance as compared to others. Being the resting place for many royal members of the Timurid dynasty, however, the Gur-I-Amir’s interior was the grandest of all that I have seen in the places I visited this time in Uzbekistan.

Perhaps the key learning about Amir Timur at his mausoleum is the fact that this was in fact not the place of his own choice in terms of a burial. He had wanted to be buried in his hometown, Shakhirsabz, and in a single tomb. The Gur-I-Amir was actually built for his grandson in 1404. Muhammad Sultan, who Amir Timur had named as the successor, died preceding Amir Timur’s own death.

When Amir Timur died in 1405, his remains could not be carried to the mausoleum in Shakhirsabz due to snow. Therefore he had to be buried in Gur-I-Amir. Thereafter, the Gur-I-Amir became the site for dynastic burial. A few of the Timurid royalties, including Amir Timur’s sons Shah Rukh and Miran Shah, and his other well-known grandson, Ulug Bek, lied in rest here.

The Mystical Powers of Amir Timur Beyond Death

Amir Timur’s learned grandson Ulug Bek, who was a well-reputed astronomer, saw through the completion of Gur-I-Amir. He acquired a large plaque of jade from Mongolia. This piece of jade was rumored to be the largest one-piece jade in the world. This jade slab contains an inscription in Arabic, “When I Rise, the World Will Tremble.” It covered Amir Timur’s coffin.

The words felt like a mighty curse and history might have proven it so as well. According to Sophie Ibbotson, a Persian invader Nadir Shah took the jade slab to Persia in 1740. Thereafter all kinds of misfortunes befell him and his son, so severely that his advisors demanded that he return the jade slab to Uzbekistan.

On June 22, 1941, a team of Russian scientists exhumed Amir Timur’s remains for scientific inquiry. Within hours, the Nazis came into Soviet Union territory.

No matter how unbelievable these stories sound, Amir Timur possessing a strong postmortem spell of the spirit is perhaps not so surprising, given the strong will that enabled him to stare down the whole world with mounted archery.

Appreciation of the Architectural Features of Gur-I-Amir

In Ulug Bek’s time, the Gur-I-Amir was a complex “containing a madrasa (religious college), and a khanqa (hospice), around a walled courtyard with a minaret at each corner” (Moya Carey). By now, the mausoleum is restored, but the original school and hospice are no longer standing, although their foundations remain. The grand entrance portal was also the work of Ulug Bek.

When you look above the mausoleum, there is a “high drum with decorative facing beath a ribbed, pointed, azure blue dome 34 meters high” (Moya Carey). The high drum feature that lies beneath the ribbed dome is unique to Central Asia’s Islamic architecture. While the mausoleum, particular its azure dome, stands proud and beautiful on the outside, the interior will take your breath away.

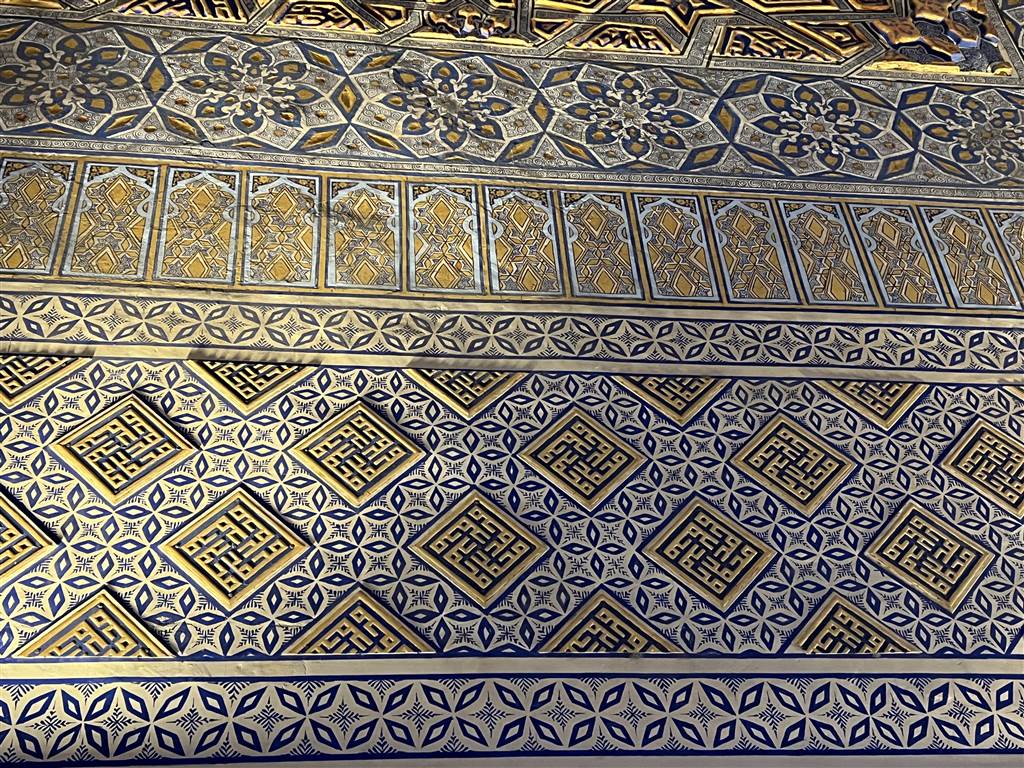

The crypt that houses the coffins of the Timurid royalties is in a square. When we entered we came to face with a grand interior glistening all over with gold. It was amazing inside the crypt.

One can immediately observe the layers of craftsmanship that makes the interior dome. On the bottom layer lies a row of glazed tiles in geometric patterns. Then comes sections of tiles, perfectly-aligned in various patterns of blue and gold. An architectural feature that is worth mentioning here is the binna’I technique, whereby glazed bricks arranged in geometric patterns are placed within groups of unglazed bricks.

On top of that layer is a band of Arabic inscriptions. The lower walls then extend upward, “rising to a cornice of muqarnas (stalactite-like decorative vaulting)” (Moya Carey). Then you would eventually look up to see the dome, that rises to an interior height of 26 meters.

We wondered about the coffins. Of the coffins inside the mausoleum, most of them show a rather petite size (especially being thin) for men. Maybe they were mummies inside? But we would not know. Uzbek men do not strike us to be small in their stature.

An Unknown Tomb and a Mausoleum in the Making

We did not think twice when the guard of a newly-constructed (or possibly restored) mausoleum space invited us to see this not-yet-named mausoleum, right outside the back door of the Gur-I-Amir. Yes, we had to pay him to get in, but again there was amazing work on the interior inside.

However, no matter how beautiful the mausoleums are, they are the chambers of death. The guard told us that the identities of the two buried in the tombs of this crypt remain yet unknown. My friend came back out of the crypt saying that it was very creepy inside. One of the remains may have belonged to a woman.

A Bowl of Lachman Can’t Go Wrong

I became very hungry when I was done at the tombs. We sat down at Kafe Jasmin. With the aid of Google I managed to ask for a bowl of veggie-only soup noodle. The veggie Lachman was very good with no mutton gaminess.

The Bahodir B&B in Samarkand

I chose the budget hotel of Bahodir B&B because of its proximity to the soul of Samarkand. It lies just about five to six minutes by walk to the Registan. When you have been touring for a long day, you would just be glad that the hotel is steps away from the touristy spots. A point of some significance is that Bahodir is the name of the 17th century Mayor of Samarkand Bahodir Yalangtush, who was responsible for reconstructing the Ulug Bek Madrasa, which was lying in ruins then, and also building the Sher Dor Madrasa anew in the Registan.

The Bahodir B&B seemed to be a family-run business. The property has quite a few rooms. I particularly liked its homey patio, where people have breakfast and gather for chats.

We checked in to our bedroom, and it was clean. The budget hotel is a bit aged, and you can tell from its general conditions, but cleanliness was my primary concern. The only problem was its shower. We learned at night that the water came out in a trickle and it was very difficult to take a shower there. If we had learned earlier, we would have requested a change of the room.

That concludes our first morning in Samarkand. So far, the city strikes us as being the favorite for local tourists. It was shoulder-to-shoulder in many places.

Sources

Moya Carey, An Illustrated History of Islamic Architecture (2012).

Sophie Ibbotson, Uzbekistan, Bradt Travel Guide (2020).

Dominique Clevenot & Gerard Degeorge, Ornament and Decoration in Islamic Architecture (2000).