War Relics at the Devil’s Peak

The Devil’s Peak has been on the top of my bucket list in terms of wartime relics. I finally had the opportunity to head out on a bright afternoon.

At a depth of 22 metres, the Lei Yue Mun Pass is very narrow and is the only maritime approach into the Victoria Harbour on the east. The Devil’s Peak, as it overlooks all of the eastern seaway into the Lei Yue Mun Pass, thus became a site of strategic importance for the British. Together with the Lei Yue Mun Fort at the highlands of Shau Kei Wan (now the Museum of Coastal Defense), the Devil’s Peak was one of the twin command centres guarding eastern Kowloon and Hong Kong on north and south of the Lei Yue Mun Pass.

The Devil’s Peak – A Brief Pre-British History

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the British built these military installations intending these structures to protect Hong Kong against potential attacks by then Britain’s European rivalries, namely France and Russia. Yet long before the British took over Hong Kong, the military significance of the Devil’s Peak was apparent to and exploited by different entities.

In early Qing Dynasty, the remnants of the Ming Dynasty took over this part of Hong Kong. The Ming loyalist forces, who were based in Taiwan and known for their sea-faring nature, occupied the Devil’s Peak. General Zheng Chenggong, the Ming loyalist warrior, led a garrison here. He extracted tolls from the commercial vessels that sailed by the Lei Yue Mun Pass. As such, the Devil’s Peak was part of the Ming Dynasty resistance against Qing rule.

Well into the Qing Dynasty, however, the Devil’s Peak was occupied by many pirates. The operators of commercial vessels often sailed through the Lei Yue Mun Pass with trepidation. For this reason, although this area was formerly named Kai Po Shan, it was known as Devil’s Peak since. There are also rumours that antique Qing treasures remain hidden in this area.

The Devil’s Peak under British Use

The British had long eyed the Devil’s Peak as a strategic military stronghold. The plan might have formed as early as 1899, or perhaps even before they officially leased the New Territories from the Qing Government. At the time, Lei Yue Mun belonged to the New Territories. The British built the Devil’s Peak Redoubt between 1900-1914.

There are four clusters of military installation. Lying at the summit, at 222 metres, is the Devil’s Peak Redoubt. At 196 metres is the Observation Post. At 160 metres lies the Gough Battery. Then finally at 80 metres lies the Pottinger Battery. We visited the Devil’s Peak Redoubt and the Gough Battery on this occasion.

On our ascent we first arrived at the Gough Battery. The major structures are two gun emplacements, one for a six-inch quick-firing gun and another for a 9.2-inch cannon. Although the gun emplacements remain intact throughout the years, the actual 9.2-inch gun was relocated to Stanley in 1936.

Photos: on the left is the 9.2-inch gun emplacement at the Gough Battery. On the right is the 6-inch emplacement.

The ruins of the Gough Battery are very photogenic. It is a pity that I visited the site before first doing my historical research. As such my pictures convey more of the aesthetics of the ruins rather than the military functions that these structures served. Do watch out for a metal ring that is pinned to the ground. Although there is no historical description, it must have served some important function perhaps for the fixation of equipment.

Photos: Views at the Gough Battery

A walk around the structures there takes about half an hour.

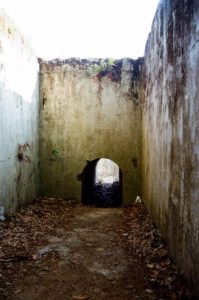

We then headed on over to the Devil’s Peak Redoubt. It occupies a very large area. Some of the structures were made of stones, but most of them were of cement.

As the Fire Command East, the Devil’s Peak Redoubt was fitted with five machine gun emplacements. They guarded the key corners of its firing wall. Furthermore, the external wall of the Redoubt has 100 loopholes providing an all-around coverage of the eastern approach to Victoria Harbour.

It was quite an experience peeping through the loopholes. I was looking on to the same view as those soldiers that guarded this stronghold at one of Hong Kong’s most critical historic moments.

As a defense structure, the Devil’s Peak Redoubt had critical facilities, including pillboxes, a communication center, a circular defense structure, and a kitchen as well. There is also a bunker on the northern cliff face of the Redoubt.

Photos: views at the Devil’s Peak Redoubt

A walk around the Devil’s Peak Redoubt can easily take an hour, especially if you go on the weekend when there are many, many tourists there competing for picture taking. This is also where all of Victoria Harbour on the west exhibits itself in a wonderful panorama. Therefore certainly allow for more time here.

Although we did not see the Pottinger Battery, I think it is worth a brief introduction. There are two gun emplacements at the Pottinger Battery, both of 9.20-inch guns. These guns relocated to the Bokhara Battery at Cape D’Aguilar. By the 1930s, all guns were removed from this battery. In the 1970s, ground filling buried one of the gun emplacements, and therefore only one remains now.

The intended plan of defense with the Devil’s Peak fortifications was complicated. These sites were connected with cement paths with pillboxes, costal search light positions and trenches. The original pathways were mostly destroyed, however. In fact, some of the communication channels became part of the Wilson Trail today.

The fortifications at Devil’s Peak, particularly the loopholes on the Devil’s Peak Redoubt, provided a 360 all-around coverage to all of the Devil’s Peak area. While the British built these fortifications during the early 1900s with their European rivalries in mind, the Devil’s Peak would only see the day of battle during World War II. Japan rose as the aggressor in Asia Pacific.

At War with Japan – British Misconceptions of Warfare during WWII

The Gin Drinkers’ line is a stretch of military defence from the western end of Kwai Chung to the eastern end of Lei Yue Mun. The Shing Mun Redoubt was another notable fortification that was intended to guard Kowloon against aggression via the land route from the north. On the eastern end, the Devil’s Peak Redoubt was part of this so-called “the Maginot Line of the East.”

The defence of Hong Kong, despite the British military’s proven prowess during the 19th century, failed miserably when the Japanese launched their invasion on Hong Kong on December 8, 1941. The Japanese forces reached the Shing Mun Redoubt on December 9, 1941. It fell into Japanese hands after just a couple days of fighting.

Similarly, the Devil’s Peak also saw some of the most ferocious battles against the Japanese.

Perhaps the Japanese caught the British by surprise in two significant ways. Firstly, the British did not fully understand that aircraft battles replaced naval battleship as the most decisive naval weapons. Secondly, the Japanese did not make a landing via the sea route, the defence of which was what the Devil’s Peak Redoubt might have been good for. Having taken down the Shing Mun Redoubt, the Japanese moved south to Kowloon. They then went eastward and approached the Devil’s Peak on land on December 13 at 4am.

At the time, the 5/7 Rajputs and the First Mountain Battery of the Hong Kong Singapore Artillery guarded the Devil’s Peak. There was heavy fighting for about twenty-four hours. The last defenders evacuated by sea to the Hong Kong Island via the Lei Yue Mun Pass.

The Japanese then took over the Devil’s Peak as the base to attack Hong Kong Island. As we all know, Hong Kong eventually surrendered to the Japanese on Christmas Day, 1941.

The View

All along the way, we saw fantastic views of the Victoria Harbour, looking westward from the eastern-most point in Kowloon. Needless the say, the higher we walked, the better the views became.

At the Devil’s Peak Redoubt, we saw panoramic views of the Lei Yue Mun Pass on the east, including the former runway of Kai Tak Airport.

It was about dusk and we enjoyed beautiful views of the Victoria Harbor. Many photographers have already reserved their spots for taking sunset pictures.

How to Get There

From the Yau Tong MTR Station exit A2, head on toward Ko Chiu Road. It is the same way up the Junk Bay Chinese Permanent Cemetery.

A gentle reminder that the walk up Ko Chiu Road is steep. Although it is only about a 20-minute walk on a paved slope, do take breaks in the pavilions on the way.

At this point, follow the sign for Wilson Trail. The stairs up the Gough Battery is on your left.

Once on the Wilson Trail, follow the signs for Devil’s Peak throughout. We headed back on the same way back to Yau Tong Station, but there is a way to leave toward Lam Tin as well.

Finally, do wear long pants. The overgrown vegetation in the area has made it hospitable for mosquitoes. Therefore also bring some mosquito repellent with you.

Sources

The majority of the historical descriptions about the Devil’s Peak in this entry came from Devil’s Peak Ruins: A Glimpse of a British Stronghold. It is a VCD made by Hong Kong University and commissioned by the Lord Wilson Heritage Trust, 2002.

See also Follow Me, Devil’s Peak.

See also Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, Leisure and Cultural Services Department, History.

Finally, see also the work of Professor Lawrence Lai, as referenced on the Wikipedia’s entry on the Devil’s Peak.

For Further Reading

This entry is part of the series on Hong Kong’s World War II history. Please visit the following links for:

Japanese Fortifications in Luk Keng

Murmurs of the Hollow at Mount Davis

Hike of the Year: From Nam Fung Sun Tsuen to Jardine’s Lookout and Back