Briefly, Nanjing – The Ming Tomb

The Ming Filial Tomb (Ming Xiaoling) had historical significance on China’s imperial burial rites. The architecture and formalities of the Ming emperor mausoleums preserved some features of their predecessors. Yet in breaking many new grounds, the Ming Filial Tomb established itself as a milestone development in imperial burials. It became the standard for all imperial burials in the Ming and Qing dynasties for five hundred years after.

In 1381, construction for the Ming Filial Tomb began. In 1398, Zhu Yuanzhang lied in rest here. Construction for all the structures completed in 1413. As the tomb of the founding emperor of Ming Dynasty, this mausoleum is the most extensive out of the nineteen Ming Dynasty imperial tombs. The other Ming tombs are spread in different regions in China, in Jiangsu, Anhui, Beijing and Hubei.

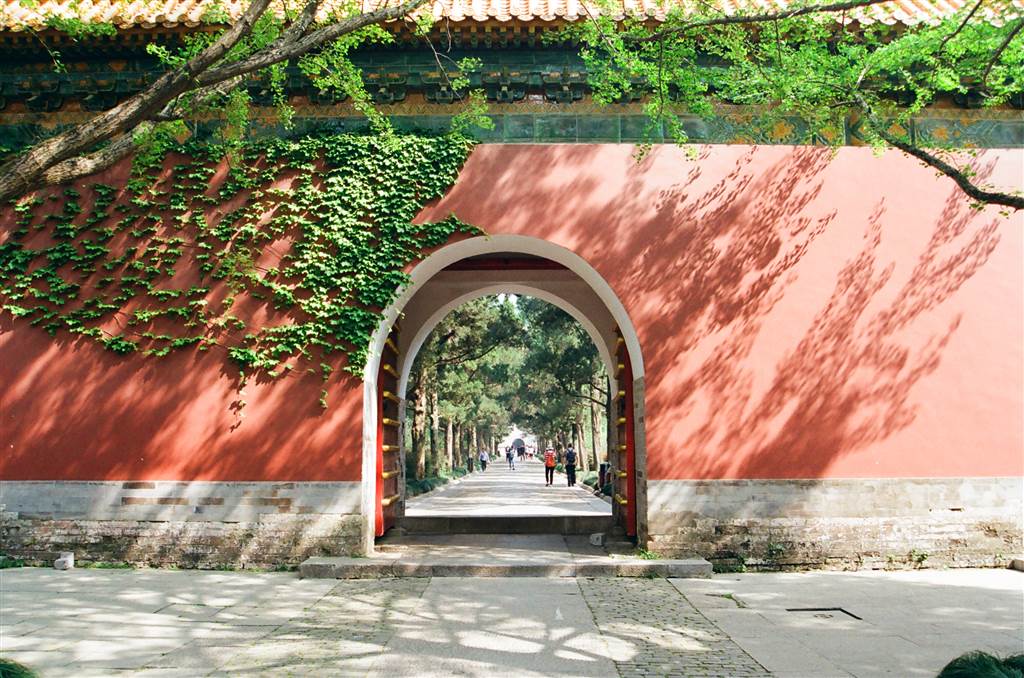

Visitors would go through the key structures on the site by walking straight on the central path. First structure to greet the visitors was the Gate of the Civil and the Military, then the Monument Hall, which was built pursuant to the order of Qing Dynasty’s Kangxi Emperor. Then the Sacrificial Hall housed the memorial tablets of Zhu Yuanzhang, his empress and the concubines. Having passed the Neihong Gate, visitors would soon arrive at the Ming Tower. Finally, one would arrive at the Treasure Mound, where Zhu Yuanzhang was actually buried.

This site presented visitors with an interesting experience. All along the central avenue I was awestruck by the grand structures. At the Ming Tower, there was a thorough exhibition showing visitors the structures and history of all nineteen Ming tombs. I was excited. Would I see something like a terracotta troop at the burial?

I walked down from the Ming Tower and came face-to-face with the burial ground. It was, for the lack of a better word, a pile of bricks. Etched onto the brick wall were the words, “here lies the Ming Taizu (Founding) Emperor.” When I saw that, I exclaimed, “that’s it?” At ground level, I was unable to view fully the circular mound that housed the remains of Zhu Yuanzhang. As such, I did not get a full perspective of the burial ground.

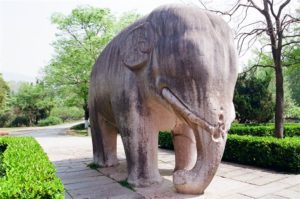

The tree-lined Scared Way had two sections. One featured twelve pairs of stone statues of six different species of animals. Shi Xiang Lu, the stone path that featured real and mystical animals, was named after the elephant, which was the largest animal on the path. The lions symbolized the authority and power of the emperor. The Xiezhi were mythological creatures that symbolized justice and fairness. The camels were animals of the desert, as such it conveyed the marvel at Ming Dynasty’s large territory. The elephants, with its enormous size, symbolized stability. The unicorns symbolized kindness and brought forth auspiciousness. Finally, the horses were the animals of warfare and victory.

The Weng Zhong path featured four civilian officials and four generals. Together the civilians and the generals guarded the dignity of the tomb. They symbolized loyalty. These statues were each carved out of one piece of stone slab. The statues were innovative because they broke with the Tang and Song Dynasties’ convention of lining the sacred way with columns. In these earlier sacred ways the carving were lotus designs on the top of the columns. Furthermore, the location of the Sacred Way was also unconventional. It did not align with the central avenue of the Ming Filial Tomb.

The original Sacred Way that led to the Ming Filial Tomb was very long, stretching all the way outside the Zhongshan Mountain National Park into Nanjing City. The two paths with stone statues captured the Ming Filial Tomb’s glory.

Next to the Sacred Way was the beautiful Sakura Garden. I could not resist its beauty and took a good walk within. Nanjing certainly cared for its gardens. I could tell that there was a careful balance between man-made structures and nature. Pagodas, pavilions and stone bridges stood amidst blooming cherry blossoms, ever so humbly. Some ladies were harvesting tea leaves from the bushes. This area was also the burial site for Sun Quan, an emperor of the Wu Kingdom during the Three Kingdoms Period.

As I passed through the Tablet Tower of Great Merits and exited the Da Jing Gate, I came upon the next site: the Soong Meiling Villa.