Briefly, Nanjing – Relearning the Taiping Rebellion

There were two reasons why I visited Zhan Yuan (Zhan Garden). First and foremost, it was only in Zhan Yuan that one could find an exhibition devoted exclusively to the history of Taiping Rebellion in China. Secondly, Zhan Yuan itself is a site of significance. At more than six hundred years, Zhan Yuan is the best preserved group of curated gardens and architecture in Nanjing that originated in the Ming Dynasty.

The Taiping Rebellion was the most significant resistance against the Qing Dynasty before the 1911 Revolution eventually overthrew China’s dynastic history. Spanning a period of twenty-five years between 1843 and 1868, the Taiping Rebellion had humble beginnings in Canton’s peasantry. The self-proclaimed Heavenly King, Hong Xiuquan, was a son of a peasant. He failed the Qing Civil Servant Examination four times.

When he met Christianity, he radicalized very quickly. Soon enough, he gathered a following by setting up the God Worshipping Society.[1] As he called himself the “brother of Jesus Christ,” he claimed to proclaim God’s will on earth. The Taiping Rebellion, meaning the Heavenly Kingdom of Peace, was considered a cult. A Christian missionary declined to baptize Hong Xiuquan. The Qing Dynasty viewed this combination of foreign religious leaning with the ability to organize to be a substantial threat. The group faced persecution by the Qing officials since its beginning as a religious sect.

However, the Taiping rebels won. Early victories against Qing persecution precipitated the rapid rise of the group as an organized resistance. Its initial success could be attributed to its banner of Han nationalism against the Qing Manchus, the reliance on religious practice to maintain discipline, rank and obedience, and the shared roots of peasantry as its identity. These features of the Taiping Rebellion has enabled the group to emerge as a political and social group. It had the ability to launch military campaigns externally and maintain order and cohesion internally. As such, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, as it so named itself, had semblance of a dynastic kingdom.

The initial success of the Taiping campaigns culminated in the proclamation of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in 1851. Hong Xiuquan named himself the Heavenly King. At that time, the generals that won the uprisings against the Qing Dynasty were given territory. Hong Xiuquan named them Lords (or emperors in Chinese). It was all looking like a feudal kingdom seeking to overthrow the Qing Dynasty.

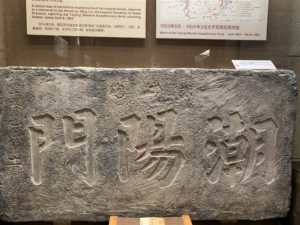

The Taiping Rebellion continued to wage successful campaigns in various strategic locations. The group took Changsha and Wuchang. Most critically, they seized control of Nanjing in 1853. Under the reign of the Taiping Rebellion, Nanjing was the Capital of Heaven (Tianjing). Thus began the Taiping Rebellion’s history in Nanjing.

In Nanjing, the people of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom lived by strict disciplines. They began their days with worship. They abided by a strict moral code as proclaimed by the Heavenly King (including the banning of all alcohol and drugs, and the segregation of the two sexes except for married couples). Staying true to its peasant roots, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom had introduced land reform. Finally, it had its own calendar, mint and currency, tax system, civil service examination, government administration and, of course, its own military. Indeed, it was so successful against the Qing Dynasty that even in its early years in Nanjing, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom received foreign convoys.

Furthermore, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom raised enormous funds to build an elaborate palace compound for the Heavenly King in Nanjing in 1854. A model of the palace compound at the exhibition gave viewers a glimpse of the Taiping Rebellion’s former glory. It is a pity that when the Xiang Army led by Qing official Zeng Guofan besieged Nanjing, the peasant soldiers burned this palace compound down to the ground as an act of revenge. As such, many of the artifacts on display were replicas. There was not much left of the Taiping Rebellion after the fire.

The success of the Taiping Rebellion garnered world attention. Both Marx and Engels have taken note of the resistance and its peasant roots. Marx had, at one point, thought it to be a very successful exercise of the proletariat revolution.[2]

As to the final downfall of the Taiping Rebellion, perhaps it was a combination of internal and external factors. The foreign powers at the time agreed to quell the movement with the Qing Dynasty. British and French-assisted campaigns weakened the Taiping Rebellion by reclaiming some of the territories. Also, the group did not win over the inland regions of China partly due to their adherence to a foreign religion. Surely, Hong Xiuquan’s death in 1864 was the harbinger for the Taiping Rebellion’s final demise.

The Taiping Rebellion as a failed resistance movement against the Qing Dynasty is perhaps not something of interest to readers of the 21st century. Yet the Taiping Rebellion has in many ways made Nanjing. Therefore the Zhan Garden was worth a visit. Finally, with view of the effects of the Taiping Rebellion on Chinese history, it has influenced Dr. Sun Yatsen by sowing the sentiments of revolution into the mind of the next great leader.

Let me now conclude this entry on the Taiping Rebellion by Dr. Sun Yatsen’s comment, “there certainly was a nationalism against Qing rule. But the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom knew nationalism without knowing the individual rights of its people. They knew the ruler but did not know democracy.”[3]

After seeing the most extensive exhibition of the Taiping Rebellion in all of China, I sat down to enjoy these following views of the Ming Garden.

My feet were beginning to swell after all that walking.

[1] This Wikipedia entry contains a more comprehensive account of the Taiping Rebellion. The story as presented in this entry is mostly based upon the museum exhibits that I saw in Nanjing.

[2] See Karl Marx in New York Daily Tribune.

[3] This comment in Chinese is wittier than its English translation because of the way that “nationalism, individual rights of the people, ruler and democracy” are said in Chinese. See the Chinese discussion here.